So, I believe that startup cities are those that amass a significant amount of potential to facilitate collision density between different kinds of thinkers. Collision density is naturally much higher in cities than in suburbs and suburban tech parks because cities house a much higher rate of diverse actors in smaller, more compact spaces. As the tools of innovation are becoming more democratized, and cities are increasingly home to dozens, if not hundreds, of accelerators, coworking spaces, fab labs, and the like, combined with proximity to artists, designers, schools, and users, entrepreneurs are able to regularly mingle with and create mashups of ideas, some of which may turn into commercializable innovations.

Emphasis added. The words "believe" and "naturally" act in tandem in this non-argument. Naturally, everyone believes collision density is higher in cities than in suburbs because Jane Jacobs didn't like sprawl. That's how the paragraph reads to me.

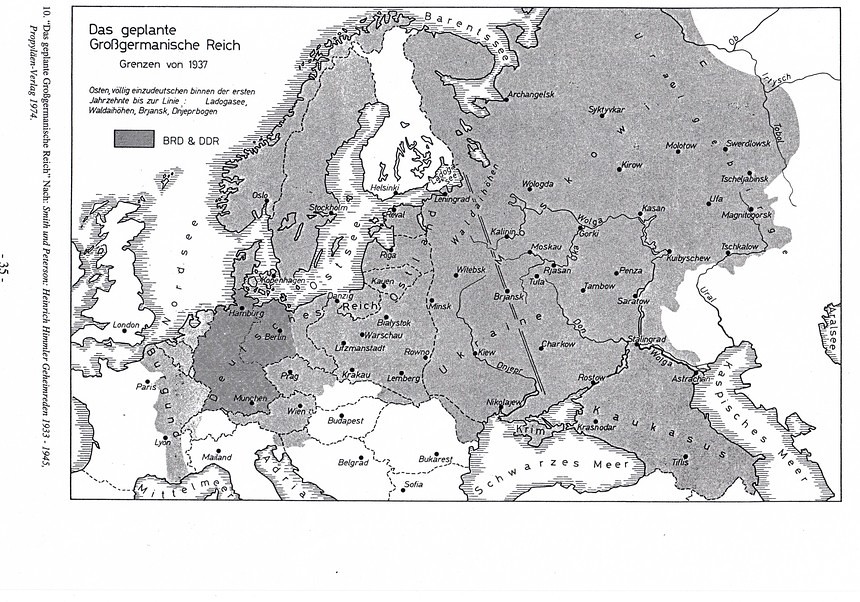

For geographers, the use of the term "natural" or "naturally" will set off the alarm of environmental determinism. Many geographers believe that environmental determinism is bad. The perspective is an academic taboo, like geopolitics. Naturally, Nazi Germany should do something about that Czechoslovakian knife sticking in the side of the Vaterland and keep going until lebensraum is restored.

Because of greater collision density, the increasing democratization of the tools of innovation will increase the commercializable innovations in cities. What does that even mean? Put a bird on it and present the model at the next International Economic Development Council conference.

The United States has a long, recent history of successful innovation and commercialization in the very places where, naturally, collision density is lacking. Believing in Jane Jacobs density won't change that fact. But democratization will? Excuse me while I pursue my manifest destiny.

2 comments:

Hi Jim, interesting post - I just read the Fastco article and came over because the notion of collision density sounds (superficially) interesting.

I'd be interested to hear you elaborate on the last paragraph - 'The United States has a long, recent history of successful innovation and commercialization in the very places where, naturally, collision density is lacking.' Where are these places? What factors enabled them to be successful?

Although there may be places in the US that are successful despite low collision density, does that necessarily preclude collision density from being part of the explanation for a location's success or lack thereof? If the implication is 'if there is collision density, then the place will thrive', then the places can still thrive without this factor, but (the contrapositive states that) places that don't thrive won't have collision density.

Hi Navaneethan,

Where are these places? What factors enabled them to be successful?

These places tended to be suburban and associated with research funded by the federal government. I recommend reading "Cities of Knowledge: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley" by Margaret O'Mara. Ironically, the lack of collision density is one of the factors that enabled these places to be successful. O'Mara makes this argument explicitly.

Federal funding + greenfields at the edge of sprawl = astounding innovation.

My take is that collision density is irrelevant. Large, dense cities are migrant magnets. Those migrants bring new ideas and networks. If they bring those new ideas and networks to exurban spaces, innovation ensues.

Post a Comment